- The Financial Brain

- Posts

- 🧠 Dividends = safe bet?

🧠 Dividends = safe bet?

Must-have or misleading?

Why do so many investors swear by dividends?

And more importantly: what are they missing by only looking at that?

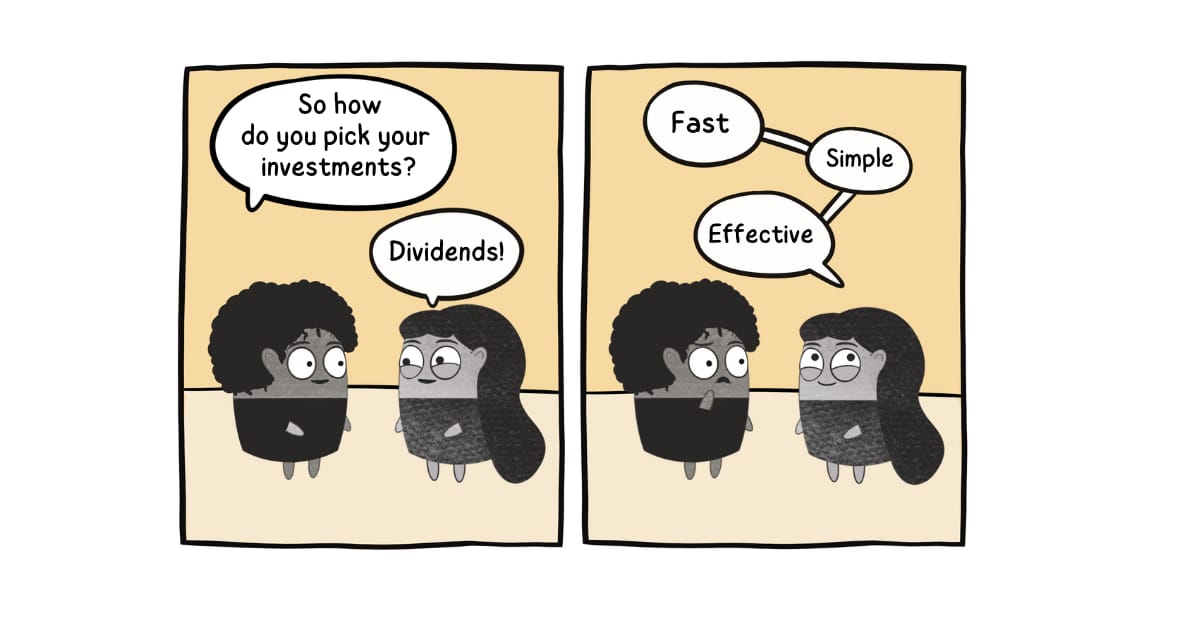

Over dinner, someone announces confidently, as if they've worked it all out:

"It’s all about dividends."

The tone is confident, almost condescending. But if you only look at one indicator, aren't you missing some blind spots?

Why we love dividends so much

First off, there are good reasons to like dividends:

It's reassuring to see actual cash landing regularly in your investment account

It lets you top up your income when it drops (spoiler: when you will retire)

It helps pay for new regular expenses (kids' education, home care or medical support for your parents)

And it gives us a mental shortcut that makes decisions easier:

"If the company pays dividends, it must be doing well. No need to dig through dozens of financial ratios or read through balance sheets and profit-and-loss statements!"

But have you checked the blind spots?

Dividends don't systematically mean the company is financially healthy.

It's a misleading shortcut. A company can pay a dividend out of habit, market pressure, or even by taking on debt. Paying a dividend is above all a management decision.

Dividends aren't guaranteed.

Companies can cut them or even stop them completely. This typically happens during sector-specific or cyclical difficulties (the hotel sector in recession, the car industry during chip shortages, the energy sector facing rising raw material costs).Some high-growth companies don't pay any.

They reinvest their profits to grow, like Amazon, Meta, or Alphabet* who scaled their companies this way.

(*This isn't investment advice, just some examples to illustrate the point.)

I'd have loved to give you more well-known European examples, but this practice is less common here than in the US.It's not "extra" money.

On the payment date, the share price drops by the same amount automatically. We've taken €5 from your left pocket and put it in your right.

But the payout in your right pocket is usually taxed, unless you live in a country where certain investment gains are exempt such as Monaco or Switzerland for long-term capital gains, or Belgium for non-speculative share sales.You're inflicting unnecessary tax on yourself.

If you don't need immediate income, you've just triggered an early tax payment.

The trap

When bond yields are low, many investors turn to high-dividend shares for regular cash. But these "high-dividend" stocks are often concentrated in sectors like banking and energy (the ones that traditionally pay the most dividends).

Vanguard warns: when your investments are concentrated in just 2 to 3 sectors, a crisis could potentially hit you harder.

For example, during the Covid shock in early 2020, shares in these sectors dropped -25%, compared to only -16% for portfolios diversified across the whole market. These sectors (banking, energy) are super-sensitive to recessions.

Vanguard researchers recommend prioritising "total return", meaning total performance (dividends + share price growth), not just the cash distributed, when building your investment portfolio.

Two phases, two approaches

When investing, there are often two main stages:

The building phase.

You're building your wealth to fund your future goals: retirement, your children's education, an important project.

These goals are still far off, so no need to withdraw money now. On the contrary: every euro reinvested speeds up your wealth growth. If you withdraw dividends each year, you slow down your progress significantly.

→ In this phase, capitalisation (via accumulating index ETFs) is more efficient: if dividends are paid, they're automatically reinvested by the fund/ETF.

Your capital grows without triggering taxes, and you're setting things up for later.

The distribution phase.

Your capital is built up, so you can either:

withdraw it all at once because it was meant to fund a big project,

or benefit from regular payments to use your wealth, to live off it partially or completely.

It's in this second case that regular income (dividends, interest) becomes really useful: you receive flows proportional to your capital, which has ideally had over one or several decades to grow.

So, dividends : good or bad idea?

It depends.

Dividends make sense if:

→ You need regular income.

→ You need the money in the short term and already have significant wealth built up.

→ You're happy to slow down your wealth growth because you prefer regular cash flow.

But if you don't need immediate cash, why make it your main criterion right now?

As always, feel free to tell me what you think of this newsletter: did it help you see things more clearly? 🙂

Take care and merry Christmas!

Nessrine

Where are you with today's topic? |

Articles, research and studies consulted for this edition:

Vanguard Research

An analysis of dividend-oriented equity strategies, June 2017Vanguard Research

Managing the low-yield environment: stay the course with a total-return investing approach, September 2021

Important reminder: This content is educational only, not investment advice. Make sure to do your own research before getting started. And remember that all investments, ETFs included, carry risks of capital loss.

Reply